In initial deals with the U.S. government, Pfizer and BioNTech's vaccine costs $19.50 per dose, compared with $15 for Moderna's shot, $16 for Novavax's program, $10 for Johnson & Johnson's vaccine and $4 for AstraZeneca's.

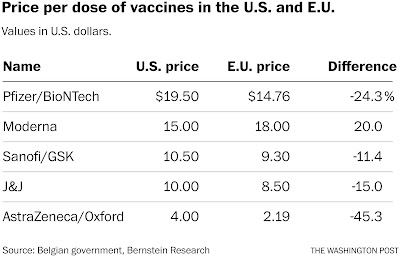

The EU is also paying less for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than the U.S., $14.70 per dose versus $19.50, according to figures reported in BMJ. On the other hand, the U.S. is paying less for the Moderna vaccine (about $15) than the EU (about $18), according to the BMJ piece. The contribution governments have made toward vaccine research is the explanation for the price differences. Moderna is charging the U.S. less for its vaccine because the U.S. government funded research that led to the vaccine’s development. Similarly, the EU supported research that led to the development of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, thus the lower price for that vaccine for the EU.

So far, governments around the world have been the only purchasers of the COVID-19 vaccines, so the price has been set by government contracts. But different countries are paying different prices. South Africa, for example, reportedly paid $5.25 per dose for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine in January, more than twice the price of $2.15 per dose paid by the European Union (EU), according to a report in BMJ. The South African government has announced that it is holding back on administering that vaccine because it may be less effective against the country’s namesake variant.

First to receive emergency use authorization in the United States, the Pfizer shot has become the world’s most popular, with 3.5 billion doses purchased. Sales could double in 2022, according to projections.

But the rapid proliferation of the vaccine, under contracts negotiated between the company and governments, has unfolded behind a veil of strict secrecy, allowing for little public scrutiny of Pfizer’s burgeoning power, even as demand surges amid new negotiations for one of the world’s most sought-after products.

A report released Tuesday by Public Citizen, a consumer rights advocacy group that gained access to a number of leaked, unredacted Pfizer contracts, sheds light on how the company uses that power to “shift risk and maximize profits,” the organization argues.

The Manhattan-based pharmaceutical giant has maintained tight levels of secrecy about negotiations with governments over contracts that can determine the fate of populations. The “contracts consistently place Pfizer’s interests before public health imperatives,” said Zain Rizvi, the researcher who wrote the report.

Public Citizen found common themes across contracts, including not only secrecy but also language to block donations of Pfizer doses. Disputes are settled in secret arbitration courts, with Pfizer able to change the terms of key decisions, including delivery dates, and demand public assets as collateral.

Sharon Castillo, a spokeswoman for Pfizer, said that confidentiality clauses were “standard in commercial contracts” and “intended to help build trust between the parties, as well as protect the confidential commercial information exchanged during negotiations and included in final contracts.”

Both Pfizer and Moderna, another U.S. company that developed a vaccine using breakthrough mRNA technology, are facing pressure from critics who accuse them of building a “duopoly.” Although Pfizer did not accept government funding through the vaccine development program called Operation Warp Speed, it received huge advance orders from the United States. It opposed an intellectual property waiver that could have meant the sharing of its technology.

Experts who reviewed the terms of contracts with foreign governments suggested that some demands were extreme. In contracts reached with Brazil, Chile, Colombia and the Dominican Republic, those states forfeited “immunity against precautionary seizure of any of [their] assets.”

“It’s almost as if the company would ask the United States to put the Grand Canyon as collateral,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of public health law at Georgetown University.

The company rejected that logic. “Pfizer has not interfered and has absolutely no intention of interfering with any country’s diplomatic, military, or culturally significant assets,” Castillo said. “To suggest anything to the contrary is irresponsible and misleading.”

Some contract demands appear to have slowed vaccine rollouts in countries. At least two countries walked away from negotiations and publicly criticized the company’s demands. However, both later reached agreements with Pfizer.

Aspects of the contracts are not uncommon, including the reliance on arbitration courts and clauses designed to give companies legal protections. Pfizer’s price for its vaccine, as low as $10 per dose in Brazil, appeared to be lower than some competitors’ prices.

“Pharma companies have concerns,” said Julia Barnes-Weise, director of the Global Healthcare Innovation Alliance Accelerator. “One of them is, especially for a not-yet-approved vaccine, that they could be held liable for any injury that that vaccine seems to have caused.”

Secret contracts

Pfizer has formalized 73 deals for its coronavirus vaccine. According to Transparency International, a London-based advocacy group, only five contracts have been formally published by governments, and these with “significant redactions.”

“Hiding contracts from public view or publishing documents filled with redacted text means we don’t know how or when vaccines will arrive, what happens if things go wrong and the level of financial risk buyers are absorbing,” said Tom Wright, research manager at the Transparency International Health Program.

Much of what is known about Pfizer’s contracts has come out in leaks, often through journalism from local outlets or international ones, including the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

Public Citizen analyzed an unredacted draft agreement between the company and Albania, as well as unredacted final documents from Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Peru and the European Commission. Redacted documents published by Chile, the United States and Britain provide further context, though they are missing key details.

The contract reached with Brazil prohibits the government from making “any public announcement concerning the existence, subject matter or terms of [the] Agreement” or commenting on its relationship with Pfizer without the prior written consent of the company.

“This is next-level stuff,” said Tahir Amin, an intellectual property lawyer who co-founded I-Mak, a nonprofit global health organization.

Pfizer exerted control over the supply of vaccine doses after contracts were signed. The Brazilian government was restricted from accepting donations of Pfizer doses or making its own donations. Pfizer also included clauses in contracts with Albania, Brazil and Colombia that it could unilaterally change delivery schedules in the case of shortages.

In contracts with Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic and Peru, governments were required to sign a document that says each “expressly and irrevocably waives any right of immunity which either it or its assets may have or acquire in the future.” The first four also were required to waive immunity against “precautionary” seizure of their assets.

Public Citizen found contracts that required governments “‘to indemnify, defend and hold harmless Pfizer’ from and against any and all suits, claims, actions, demands, damages, costs and expenses related to vaccine intellectual property.”

An opaque giant

Pfizer has not experienced the same level of public scrutiny as Moderna, which has been accused of price-gouging and delaying deliveries. Analytics firm Airfinity this week predicted Pfizer will sell $54.5 billion worth of coronavirus vaccine next year, almost twice the value of Moderna’s sales.

One official from a country in the midst of negotiations with Pfizer, who was not authorized to speak on the matter, said that the country found Pfizer difficult to negotiate with but reliable in the delivery of vaccine doses.

Like Moderna’s, Pfizer’s vaccine has been found to be highly effective against the delta variant of the coronavirus and to provide long-lasting immunity. From the leaked documents, Pfizer appears to have offered lower prices for its vaccine to poorer countries that had less leverage.

Castillo said that Pfizer had committed to a tiered pricing approach, with wealthier nations paying about the cost of a takeout meal per dose and lower-middle-income countries offered prices at a not-for-profit price. Some 99 million doses had reached low- and lower-middle-income countries so far, and the company expects “substantial increase in shipments to these countries through the end of the year.”

Contract terms related to sovereign immunity may have been an attempt to cover for some risks over which the company has little control, including the use of new, unapproved vaccines in partner countries where the company has little oversight over storage and distribution. Pfizer may have been worried about opportunistic lawsuits in countries where it had not filed patents, Barnes-Weise said.

Some countries, including the United States, have laws that provide indemnification to vaccine manufacturers, but most do not.

However, Transparency International argued that at least four contracts or drafts it examined went “much further” than other vaccine developers, with “more of the risk onto national governments, and away from the developer, even if missteps are made by the developer or supply chain partners, and not just if there is a rare adverse effect of the vaccines.”

Suerie Moon, co-director of the global health center at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, said that restrictions on donations were “appalling” and “counter to the goal of getting vaccines as quickly as possible to those who need them.”

Castillo said Pfizer is not currently pursuing legal action against any government related to its coronavirus vaccine.

At least two countries that initially backed out of negotiations with Pfizer later returned. In January, Brazil publicly said Pfizer was insisting on “unfair and abusive” contractual terms, pointing to the confidentiality clauses. Just months later, Brazil signed a $1 billion contract with the drug giant for 100 million doses. Public Citizen says that the signed contract, later leaked, contained many of the provisions that Brazil once opposed.

Argentina also rejected early negotiations with Pfizer, with the country’s former health minister publicly saying the company “behaved very badly” and was making demands that did not comply with Argentine law. The country later agreed to purchase 20 million doses. The unredacted contract has not been released.

Covax, a World Health Organization-backed vaccine-sharing initiative, has purchased only a relatively modest 40 million doses directly from Pfizer, with reports of disputes during subsequent negotiations. Covax later reached an agreement with the United States for Washington to buy and redistribute 500 million Pfizer doses to low-income countries through Covax.

In its report, Public Citizen called on the U.S. government to use its leverage to force Pfizer to take a different approach, including requiring the company to share technology and intellectual property so that other manufacturers can produce the vaccine.

“The global community cannot allow pharmaceutical corporations to keep calling the shots,” Rizvi said. “The Biden administration can step up and balance the scales.”